By Timothy Kalyegira

Independence came at the start of the 1960s following, in the 1950s, a decade of the largest and most consequential industrial and infrastructural expansion in Uganda’s history, and on which the country remains essentially rooted 59 years later.

From the Owen Falls Dam and Nile Breweries at Jinja, to Kilembe Mines in Kasese, Uganda Electricity Board, Tororo Cement and the Uganda Development Corporation, if there was a decade in which the idea of a national development plan was put in place, that was the 1950s.

The Uganda of 1962 was a multi-cultural society. European civil servants dominated education, health and parts of the civil service.

Indian sub-continent Asians were prominent in trade and some areas of medicine and academia.

Nonetheless, indigenous Ugandans were starting out to enter the civil service and agriculture.

Two political parties, the Democratic Party (DP) and the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC), dominated the political landscape in their reflection of the fundamental cultural identities of the country, religion and ethnicity.

Almost all education institutions were run by the government or religious denominations.

And the country’s main export earnings were the traditional commercial crops of coffee, cotton, tobacco and tea.

Social polity

Buganda then sat solidly at the centre of national life as the predominant cultural, ethnic and political entity in Uganda.

Politically, Buganda was also the hotbed of political agitation, drama and confrontation with the colonial government. It was also the only part of Uganda that felt most impatience for Independence.

The rest of the country participated in politics more like a civic, Rotary-like polite duty.

By then, Uganda had not yet experienced any modern, armoured war on its territory.

Various districts still had British officers as police commanders. The broadcast media consisted of only Radio Uganda and television was still one year away. But the newspaper market was much more diversified and had several English- and Luganda-language titles.

The entry fee to Kampala’s nightclubs was Shs2, with the more upscale clubs charging Shs3.

A kilogramme of meat sold for Shs1 and 50 cents, a bunch of matooke went for Shs3, and a kilo of sugar cost 30 cents.

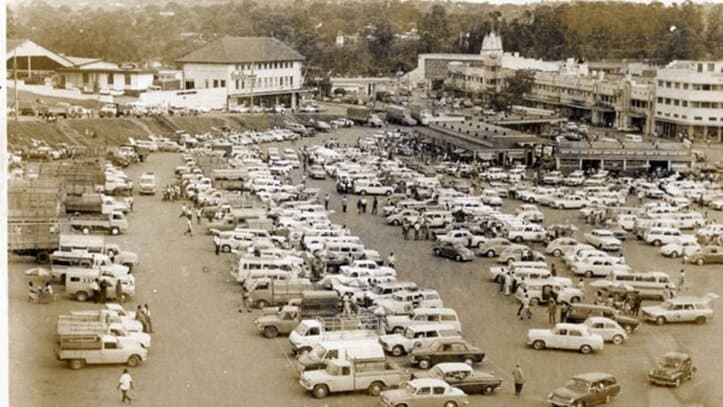

By then, Jinja was the industrial heart of Uganda and Busoga in general was the main area of commercial agriculture, mostly sugarcane and tea.

Jinja in the 1950s was a European town in its design, facilities and the composition of the technocratic workforce, and Tororo, originally planned by the colonial government as the second industrial town after Jinja. By then, Tororo was a vibrant town, its street and residential layout resembling that of Jinja.

Mbale, largely an Indian town, was halfway between being a Jinja and Tororo, with an Indian mayor, and was the centre of the country’s coffee-growing and processing industry.

In general, apart from Buganda, Uganda was a boring country in the way we think of, say Zambia or Mauritius.

Uganda after 1962

The first two years of Independence looked like a continuation of the 1950s decade. But 1964 can be seen as the year Uganda started becoming the country it is today, although in 1963, the first armed insurrection formed in the Rwenzori area of western Uganda, as the Rwenzururu Movement agitated for a degree of autonomy.

But more trouble erupted in January when the armies of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda mutinied.

The unlikely alliance between the Socialist-leaning UPC and the monarchist Kabaka Yekka party continued to hold, until it fell apart in 1964 when the UPC co-opted a section of the DP in Parliament, including the Leader of the Opposition, Basil Bataringaya.

But after 1964, the bland, technocratic image of Uganda started to give way to politics and intrigue as the staple of national life.

This atmosphere of political intrigue reached its climax in May 1966, when growing tensions between the government and the Kabaka’s administration at Mengo resulted in a military operation against the Kabaka’s palace at Lubiri, on the outskirts of Kampala city.

Uganda’s history from 1966 to 2021, has largely been a tale of a reaction against the perceived illegitimacy of the central government.

There has never been a general election that has not been bitterly contested and its results rejected by the losing side.

The closest since 1966 that Uganda’s political class has ever come to a common position on the major issues of the day was in 1977 after the death of the Anglican Archbishop Janani Luwum, with the majority of the elite and civil society agreeing that Idi Amin was a danger and disgrace to Uganda.

Once the 1978-1979 Tanzania-Uganda war had toppled Amin in April 1979, the country was thrown back once more into its late 1960s mentality of intrigue and factional fighting.

The 1962 to 1986 period was broadly viewed by the southern Bantu tribes as one of oppression, military brutality and nepotistic domination of the State by northerners.

Similarly, the 1986 to 2021 period has been viewed by the northern Nilotic and Nilo-Hamitic tribes as one of military brutality, oppression and tribal rule by southerners.

A significant new development over the last 35 years has been the shift, for obvious reasons, of the political and military centre from northern Uganda to south-western Uganda, bypassing Buganda and leaving eastern Uganda feeling ignored.

However, since 2001, Buganda has increasingly been expressing irritation with the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party government.

This animosity was refined from one of northerners against southerners to one of Uganda versus westerners.

Previously, in the 1950s, everyone resented Buganda’s dominance and perceived arrogance, but today, the tables have turned, with the focus of broad national resentment trained on the west of Uganda.

The economy

Amid all the political infighting, bitterness and contestations for State power, the foundation of the economy has remained more or less the same as it was nearly 60 years ago.

In spite of the expansion in formal education and the number of schools and universities, agriculture continues to be the backbone of the economy and practically all export earnings are from raw commodities.

Even tourism, said to be a significant new growth area, is as it was in the 1950s, with most inbound tourists being Americans and Europeans.

1973 – 1993 economic crisis

During the 20-year period of economic crisis and scarcity between 1973 and 1993, demand far outstripped supply in almost every area of the economy except basic foodstuffs.

From toilet paper to basins, mattresses, soda, pharmaceutical and veterinary drugs, toothpaste, sugar, soap, cooking oil and salt, everything always seemed in short supply.

Today, Uganda faces the opposite crisis: Too much effort and resources were expended in trying to address the supply bottlenecks in the economy, little work was put into addressing the demand-side.

As a result, supply now significantly exceeds demand, with empty hotels, high-rise office buildings and apartment blocks in Kampala and the five major upcountry towns.

Connectivity and the airwaves

There are more radio and television stations than the advertising market can support.

There is also an oversupply of graduates from the 30 or so universities for a labour market that shows little expansion.

A large number of Ugandans now work in the Persian Gulf states at menial jobs.

The country’s failure since Independence to develop true internal productive, research, financial and management capacity, has left it heavily dependent on foreign capital to sustain the economy.

Nearly six decades after Independence, there are very few Ugandan companies that are able to stand unsupported by political patronage, and with every change of government, an entire category of companies goes out of business.

The last 25 years have seen Uganda enter the global hyper-linked computer network called the Internet.

And hopes that access to this global, relatively cheap communication, publishing and business network would provide an additional driver of growth to the Ugandan economy have largely been dashed.

While it has increased access to communications across the country and made them instant and affordable, little of that has translated into actual economic development.

But one positive outcome of the Internet has been not only in increasing the number of mainstream professional media outlets, but also creating an entire ecosystem of rumours and conspiracy theories.

As governments have since 1966 become increasingly intolerant of criticism of their policies and human rights records, there was a need for lone and brave voices to speak out.

In the print and analog broadcast era until the late 1996s, alternative media was an expensive and dangerous venture.

The Internet has enabled an assortment of whistleblowers and truth-tellers to publish and distribute at a minimal cost and to much wider local and international audiences.

The myriads of smartphones in many pockets and hands at any one time in Uganda, makes it hard for certain documents and acts of brutality to be hidden or covered up.

As a result of the Internet’s anonymity and affordable publishing, much of Uganda’s secret political history has finally come to light.

We now know much more about the 1970s and 1980s under Idi Amin and Milton Obote than we did at the time, and for decades later, both what is blamed on the rulers, and also on the guerrillas bent on tarnishing the regime’s image.

We also now know that the generic figures of 500,000 allegedly killed under Amin and 300,000 killed under the second Obote government can be openly challenged.

We also now know, from the narratives on Luweero Triangle Bush War, that both soldiers of then sitting government and rebels committed atrocities.

Finally, we also now know that the same narrative applies to the atrocities committed in both Teso and Acholi during insurgencies in the sub-regions in the late 1980s and during the 1990s.

Similarly, the legend the NRM government carefully constructed for decades about its historical mission has come to be undone in public view.

The emergence from the shadows of Uganda’s true, secret political history has been one of the most important developments of the past 59 years.

To sum up, Uganda remains essentially the same country that anybody alive in 1962 would have recognised.

It is a Third World country, a sub-Saharan African country that does not yet have a clear idea of its place in the world. It often tries to punch above its weight, but lacks the discipline and capacity to match its words with results.

But the country has blended much more with more intermarriage across tribe today than was usually tolerated in the 1950s.

But Buganda remains the restless, dissatisfied power and influence at the geographical centre, although less effective at exerting its voice.

The culture is still the same as it was in the 1940s and 1950s, deferring to authority, impressed more by appearances than substance, the people friendly but undisciplined as always, and generally, but hopeful about the future.

Background-Comparative figures

Population: 1962: 7.21 million

2020: 45.74 million

GDP: 1962: $4.06 billion

2020: $37.37 billion

GDP per capita, 1962: $563.8

2020: $817.04

Exports: 1962: $0.996 million

2020: $5.62 billion

SOURCE: World Bank / Bank of Uganda reports